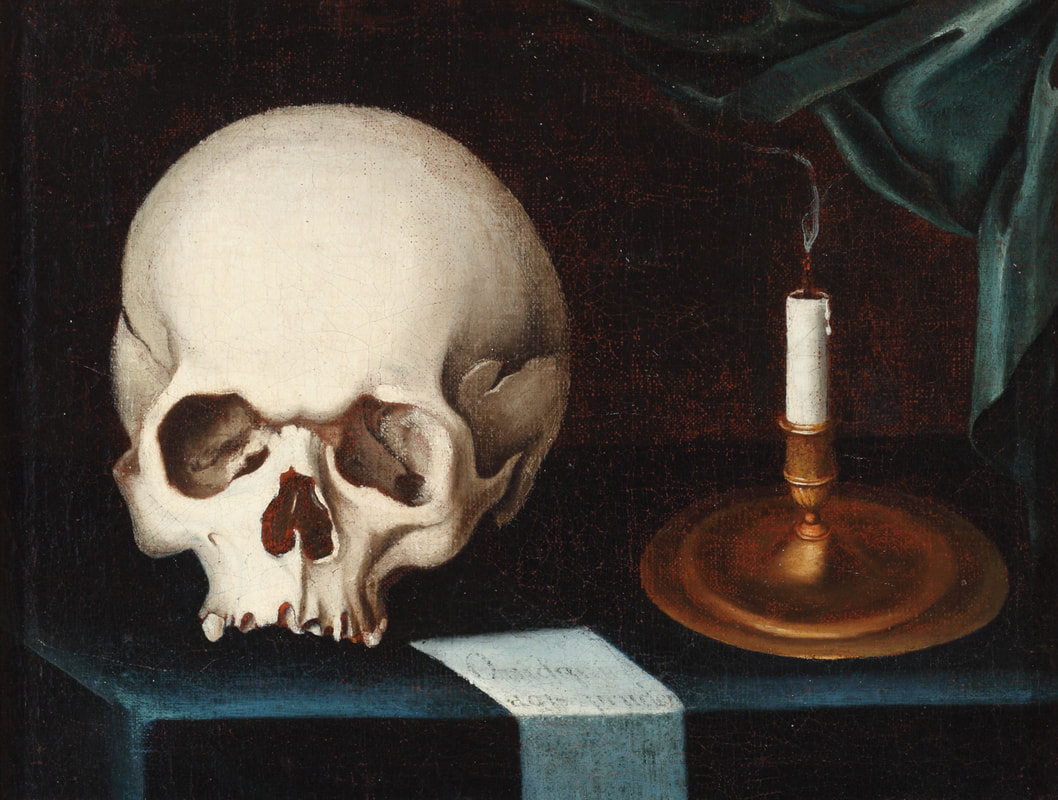

F. Friderich, German, Active late 18th century, Vanitas, 1774, Oil on canvas, 13 x 17 in., Saint Vincent Archabbey Collection, Gift of King Ludwig I of Bavaria. Photo: Richard Stoner.

Created over 100 years after its popular emergence in the early 17th century, this still-life couples a human skull with a snuffed-out candle alluding to the words of Psalm 52, “My days are consumed like smoke.” The Latin script separating the items records the first few words of the phrase: Quid quid agis, prudenter agas et respice finem, or, Whatever you do, do it with intelligence and with the end in mind. Elements of this concentrated vignette were conceivably sourced from a mid-18th century mezzotint by Johann Elias Ridinger. While no biographical information of the artist is known, given the provenance of the collection, it is probable Friderich was Bavarian like Ridinger.

The vanitas still-life emerged as a popular subject in Northern Europe whereby a lexicon of virtues and vices were assigned to a host of objects each symbolizing a moral imperative. These paintings functioned as memento-mori, or visual reminders that life is inherently terminal and the behaviors of today will follow the believer in the hereafter. Other 17th century works incorporating the human skull included portraits, genre scenes, as well as historical and religious painting– offering artists a moralizing motif that infused the trappings of the tangible world with the foresight that life, by its nature, is fleeting. Audiences at this time were aware of the symbolic implications of these visual contemplations on mortality. The vanitas effectively visualizes Saint Benedict’s warning, “Remember to keep death before your eyes daily” (RSB 4.47); a precept that encourages an open and receptive attitude towards life even in the face of death.

The vanitas still-life emerged as a popular subject in Northern Europe whereby a lexicon of virtues and vices were assigned to a host of objects each symbolizing a moral imperative. These paintings functioned as memento-mori, or visual reminders that life is inherently terminal and the behaviors of today will follow the believer in the hereafter. Other 17th century works incorporating the human skull included portraits, genre scenes, as well as historical and religious painting– offering artists a moralizing motif that infused the trappings of the tangible world with the foresight that life, by its nature, is fleeting. Audiences at this time were aware of the symbolic implications of these visual contemplations on mortality. The vanitas effectively visualizes Saint Benedict’s warning, “Remember to keep death before your eyes daily” (RSB 4.47); a precept that encourages an open and receptive attitude towards life even in the face of death.