The Global Exchange of Art and Aesthetics

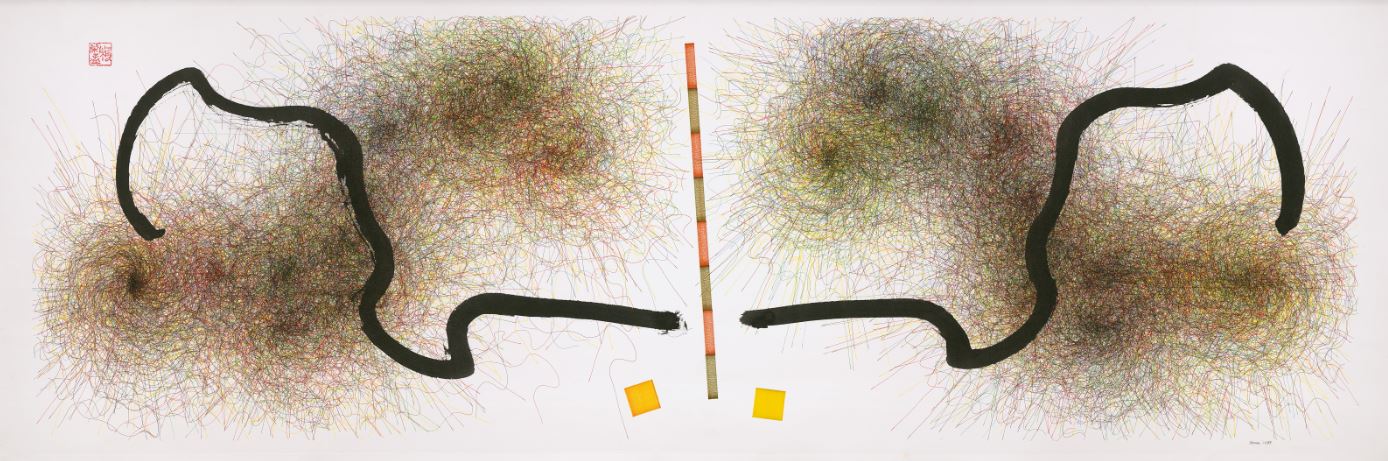

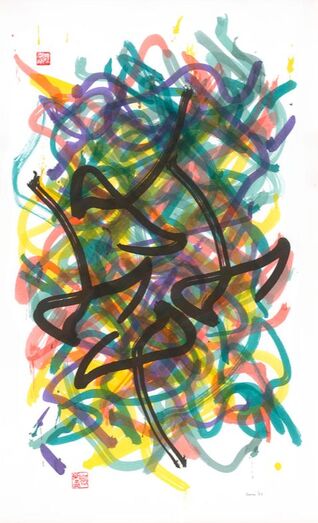

The Lung Shan work is more than expressionist brush work. It includes the conjunction of both rational and non-rational elements: control and un-control, something akin to yin- yang, light and shadow, hard and soft, sweet and sour—the Chinese genius for the marriage of opposites.

Verostko, “Dragon Mountain: East & West joined in Algorithmic Art”

Verostko’s travels to China, first in 1982 and again in a teaching capacity in 1985 and 1998, had a remarkable influence on his development as an artist. And he, in turn, introduced twentieth-century Western art to a group of young Chinese artists eager to expand their understanding of different aesthetic traditions. The academic exchange initiated by the Chinese artist Zheng Shengtian introduced Verostko to the master calligrapher Wang Dongling, who followed Verostko’s art history course. The subsequent friendship and artistic interchange between Verostko and Wang Dongling resulted in each artist’s unique combination of different media, materials, and methods for producing brush lines.

While in New York in the early 1960s, Verostko practiced brushwork influenced by abstract expressionists whom he had known personally, such as Franz Kline, George McNeil, Barnett Newman, and Robert Richenburg. In this regard, he was familiar with Eastern thought and aesthetics that had a profound effect on the New York School after World War II. Verostko was particularly interested in the magazine It Is, published by Philip Pavia between 1958 and 1965, which featured art, poetry, and other writing focused on the pure phenomenon of the concrete work itself. The presence and physical reality of the picture field were everything. It was not until the 1980s, however, when Verostko learned more about medieval Zen through his travels and personal China connections, that he came to realize the kinship between the concept “it is” and the Chinese calligraphic brushstroke.

After returning from China in 1985, Verostko established what he would call his “Pathway Studio.” He gained access to his first pen plotter, a HI DMP52 with fourteen pen stalls, and began translating his algorithms for computer monitors into routines for guiding the drawing arm of his pen plotter. The idea of coding for the brush soon followed as he adapted Chinese brushes to fit the drawing arm of the plotter. His first algorithmic brush painting, Untitled #81, executed with a brush he brought from China, dates from early 1987. Works in the Pathway series that followed in 1988 couple brushstrokes with clusters of pen strokes based on similar form structures. The influence of calligraphy is evident in the vertical orientation of brushstrokes as well as the “no-character” calligraphic mark making (feizi ).

While in New York in the early 1960s, Verostko practiced brushwork influenced by abstract expressionists whom he had known personally, such as Franz Kline, George McNeil, Barnett Newman, and Robert Richenburg. In this regard, he was familiar with Eastern thought and aesthetics that had a profound effect on the New York School after World War II. Verostko was particularly interested in the magazine It Is, published by Philip Pavia between 1958 and 1965, which featured art, poetry, and other writing focused on the pure phenomenon of the concrete work itself. The presence and physical reality of the picture field were everything. It was not until the 1980s, however, when Verostko learned more about medieval Zen through his travels and personal China connections, that he came to realize the kinship between the concept “it is” and the Chinese calligraphic brushstroke.

After returning from China in 1985, Verostko established what he would call his “Pathway Studio.” He gained access to his first pen plotter, a HI DMP52 with fourteen pen stalls, and began translating his algorithms for computer monitors into routines for guiding the drawing arm of his pen plotter. The idea of coding for the brush soon followed as he adapted Chinese brushes to fit the drawing arm of the plotter. His first algorithmic brush painting, Untitled #81, executed with a brush he brought from China, dates from early 1987. Works in the Pathway series that followed in 1988 couple brushstrokes with clusters of pen strokes based on similar form structures. The influence of calligraphy is evident in the vertical orientation of brushstrokes as well as the “no-character” calligraphic mark making (feizi ).

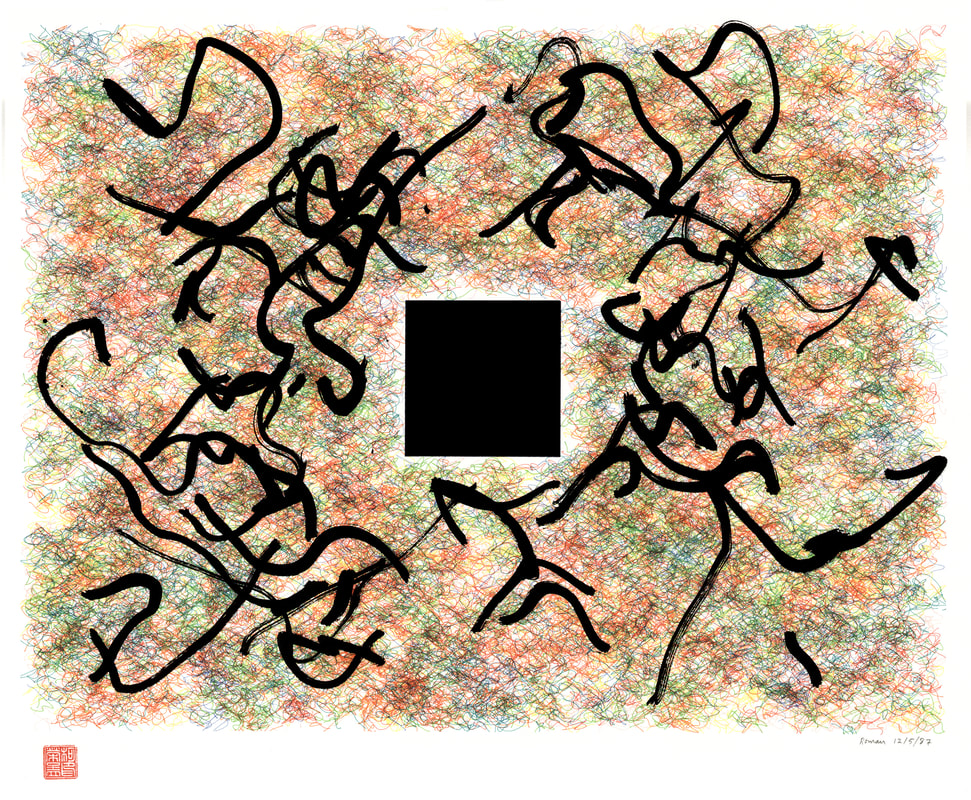

Untitled #81, 1987, pen, ink, and brush plotter drawing, 24 x 19 in

This work represents routines used in the earliest plotter drawings. These routines were derived from the earlier work, The Magic Hand of Chance (1982–85). The origins of the software procedures may be found in abstract expressionism and earlier forms of twentieth-century automatism. The artist’s own prototypes are found in his work at Saint Vincent Archabbey.

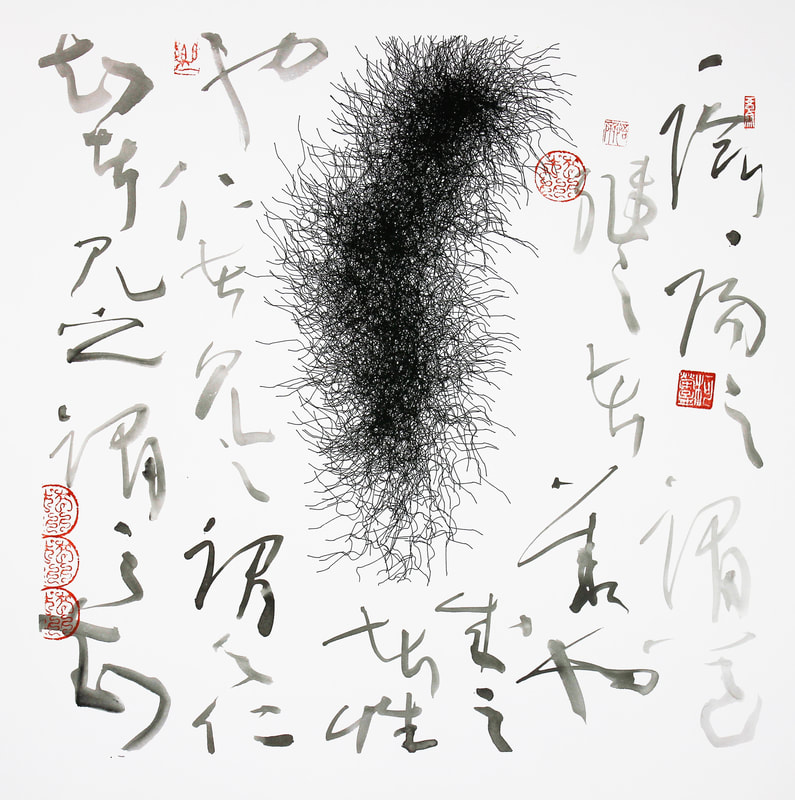

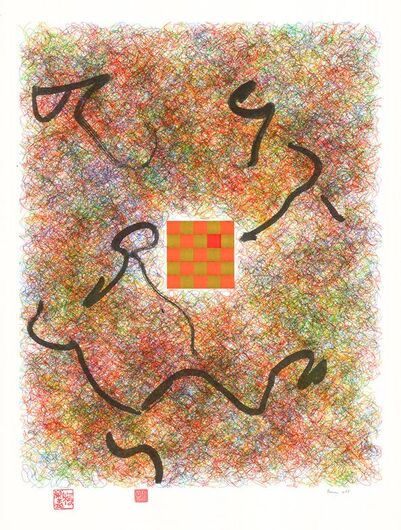

Follow the Way of Yin and Yang, 1988, pen plotter drawing by Verotsko and calligraphy by Wang Dongling

Text translation of Wang Dongling’s calligraphy: Those who follow the way of Yin and Yang are righteous; those who accomplish it carry its nature within themselves. Those who are benevolent see its benevolence; those who have knowledge within themselves perceive its knowledge. Quoted from the I Ching, or Book of Changes.

This joint work between Verostko and Wang took place in 1988 when Wang was a visiting professor at the University of Minnesota and lived with Verostko and Alice for several months. The algorithmic plotter drawing was made first and the calligraphic addition was Wang’s response.

Text translation of Wang Dongling’s calligraphy: Those who follow the way of Yin and Yang are righteous; those who accomplish it carry its nature within themselves. Those who are benevolent see its benevolence; those who have knowledge within themselves perceive its knowledge. Quoted from the I Ching, or Book of Changes.

This joint work between Verostko and Wang took place in 1988 when Wang was a visiting professor at the University of Minnesota and lived with Verostko and Alice for several months. The algorithmic plotter drawing was made first and the calligraphic addition was Wang’s response.

|

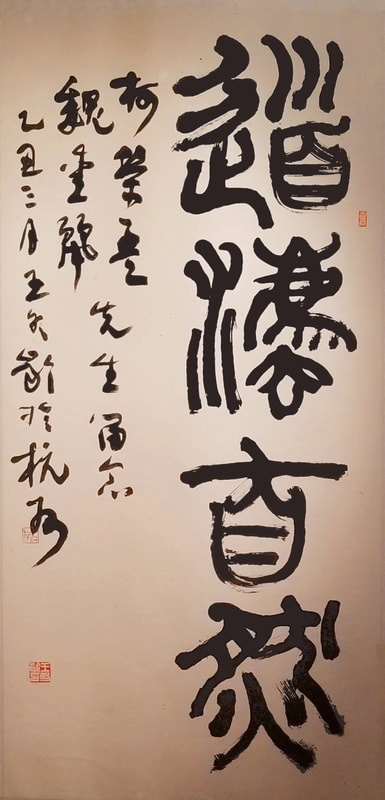

Wang Dongling

Untitled, 1985 ink on paper, mounted on silk, 85 1/4 x 29 5/8 in. (scroll); 52 1/2 x 25 in. (paper) This scroll was created for Verostko and his wife, Alice, toward the end of Verostko’s teaching session at the China Academy of Art in spring 1985. Text translation: (column far right) 道 Tao 法 follows 自 然 Nature |

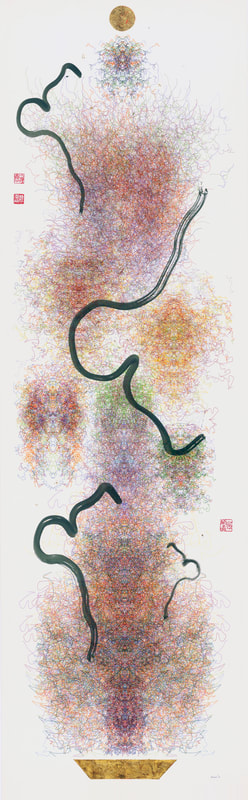

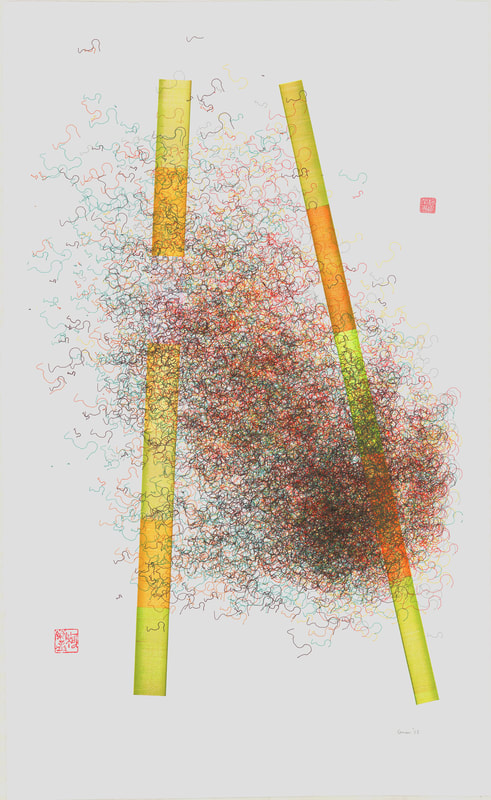

Aladdin’s Lamp, 1991, pen, ink, and brush plotter drawing with hand- applied gold leaf,

84 x 29 1/2 in. |

Lung Shan II (Dragon Mountain), 1989, pen, ink, and brush plotter drawing, 72 x 24 in.

The brush adapted for the drawing machine for this work was given to Verostko when he taught in China in 1985. The artwork displays the influence of Asian calligraphy. Verostko was also inspired by Wang Dongling, who lived in Verostko’s home when he was a visiting professor at the University of Minnesota in 1988–89. Wang also followed that course that Verostko taught at the China Academy of Art in 1985. This work is one of two versions with the title Lung Shan, meaning “dragon mountain.”

Masquerade, 1988, pen and ink plotter drawing, 24 x 39 1/4 in.

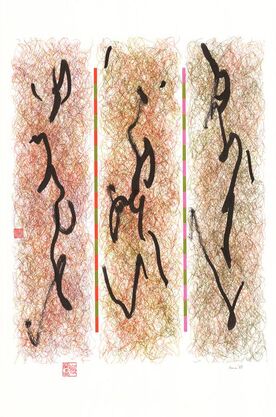

Gaia Triptych

Coded drawing procedures, much like a musical score, embody form generating ideas. As with music, I believe we can create “scores” for drawing that evoke emotional and spiritual experience. This work enshrines the procedure by which it was made. The strokes celebrate the code for its “form-generating” processes that bear some similarity to those present in biological growth. By doing so it provides a window on unseen processes shaping mind and matter, an icon illuminating the mysterious nature of earth and cosmos.

Gaia Triptych II (closed), 1991, pen, ink, and brush plotter drawing with hand-applied gold leaf, 41 x 38 1/4in. Photo: Richard Stoner

This triptych, structured like a folding altarpiece, may be viewed in either the open or closed position. Such folding panels were used in Europe in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance for liturgical purposes. The Isenheim Altarpiece, for example, could be open to show the Crucifixion during the Lenten Season then switched to the Resurrection on Easter Sunday.

Gaia Triptych II (open), 1991, pen, ink, and brush plotter drawing with hand-applied gold leaf, 41 x 79 in. Photo: Richard Stoner

For the five panels comprising this work, well over 50,000 starting coordinates and over half a million control points were plotted to within one thousandth of an inch. The specific form of the panels was realized with code driven improvisations based in an initiating set of control points. These initial “controller” coordinates, randomly cast, can be seen in the side panel brush strokes that mirror each other. Form transformations achieved through reflections of the same form in several directions may be seen in the center panel and in the back panels (closed position). All the work, including color decisions, was software generated except the gold leaf, which was applied by hand.

|

Verostko, 1991

|