The Resolution of Opposites: Chance and Control in the Search for Pure Form

I’m interested in the philosophy of chaos. Chaos and apparent chaos, the random and the pseudo-random elements. I like to juxtapose the stable and the chaotic.

|

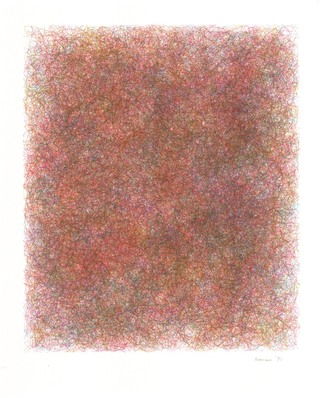

Verostko, 1989

|

One of the most salient characteristics of Verostko’s lifelong engagement with art as a maker and historian is his understanding of human experience vacillating between the poles of chance and control. His exploration of spontaneous automatic drawing techniques and rational mark making that began in the early 1960s when he was living in New York City and Paris played a key role in his attraction to and application of emerging audiovisual and computer technologies to the art-making process. The harmonizing of visual opposites in the New City series, the oscillation of non-repeating routines in The Magic Hand of Chance, and the improvisation within strict parameters written into Verostko’s master algorithmic code are not superficial aesthetic choices. Rather, they represent for the artist a spiritual struggle, an acknowledgment that peace and unity lie in the balance between reason and feeling—between all the interior forces that push and pull in opposite directions.

The tension between carefully thought-out “line-making” decisions and the spontaneous flow of the pen or the expressive gesture of the brush is evident in works ranging from his Eikons to his coded algorithmic procedures in Heaven and Earth to his newest Digital Transformations. These works represented a quest for art objects that could lead to an interior experience that transcends the material object. Just as the goal of the paintings and drawings in Verostko’s pre-algorist work was to bring forth images of the “unseen” from those segments that lay hidden from our conscious self, similarly his algorist works attempt to create visual worlds that can stand on their own without reference to other reality.

The tension between carefully thought-out “line-making” decisions and the spontaneous flow of the pen or the expressive gesture of the brush is evident in works ranging from his Eikons to his coded algorithmic procedures in Heaven and Earth to his newest Digital Transformations. These works represented a quest for art objects that could lead to an interior experience that transcends the material object. Just as the goal of the paintings and drawings in Verostko’s pre-algorist work was to bring forth images of the “unseen” from those segments that lay hidden from our conscious self, similarly his algorist works attempt to create visual worlds that can stand on their own without reference to other reality.

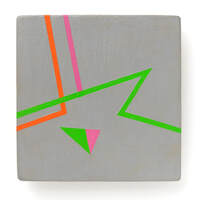

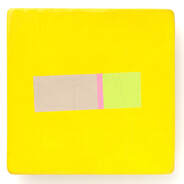

The New City, 1968, mixed media on wood panel primed with gesso, 48 x 48 in.

The New City series, which consists of paintings ranging in size from 24 x 24 in. to 8 ft. x 8 ft., brings opposing visual elements into a relationship of dynamic equilibrium. By merging spontaneity and rational control in the same work, Verostko attempted to achieve the equilibrium he sought in his spiritual life.

The New City series, which consists of paintings ranging in size from 24 x 24 in. to 8 ft. x 8 ft., brings opposing visual elements into a relationship of dynamic equilibrium. By merging spontaneity and rational control in the same work, Verostko attempted to achieve the equilibrium he sought in his spiritual life.

Crucifix, 1962, acrylic, clay, wood, 14 x 14 in. Photo: Rik Sferra

Sunrise on West 34th Street, 1962

oil on canvas

After being ordained a priest, Verostko was sent to New York City as a resident monk at Saint Michael’s rectory on West 34th Street. His mission was to pursue both studio and academic studies and to return to Saint Vincent Archabbey to enrich a program in the arts. This is one of Verostko’s earliest non-referential works.

oil on canvas

After being ordained a priest, Verostko was sent to New York City as a resident monk at Saint Michael’s rectory on West 34th Street. His mission was to pursue both studio and academic studies and to return to Saint Vincent Archabbey to enrich a program in the arts. This is one of Verostko’s earliest non-referential works.

Psalms in Sound & Image: Lovesong, 1967, electronically synchronized audiovisual presentation with sound track by Daniel Lenz. Soprano: Phyllis Bryn Julson recorded at Tanglewood in 1966. This video conversion was recorded in 2018 from a playback of the original slides and synchronized soundtrack. 9:00 min.

Verostko’s Psalms in Sound & Image were presented at numerous colleges and universities between 1966 and 1968 including: Marymount Manhattan College, New York City; Yale Disciple’s House, New Haven, Connecticut; Duquesne University, Pittsburgh; Seton Hill College, Greensburg, Pennsylvania; St. Scholastica College, Atchison, Kansas; St. Mary’s College, Convent Station, New Jersey; Fisk University, Nashville, Tennessee; and Loyola University, Chicago.

Verostko’s Psalms in Sound & Image were presented at numerous colleges and universities between 1966 and 1968 including: Marymount Manhattan College, New York City; Yale Disciple’s House, New Haven, Connecticut; Duquesne University, Pittsburgh; Seton Hill College, Greensburg, Pennsylvania; St. Scholastica College, Atchison, Kansas; St. Mary’s College, Convent Station, New Jersey; Fisk University, Nashville, Tennessee; and Loyola University, Chicago.

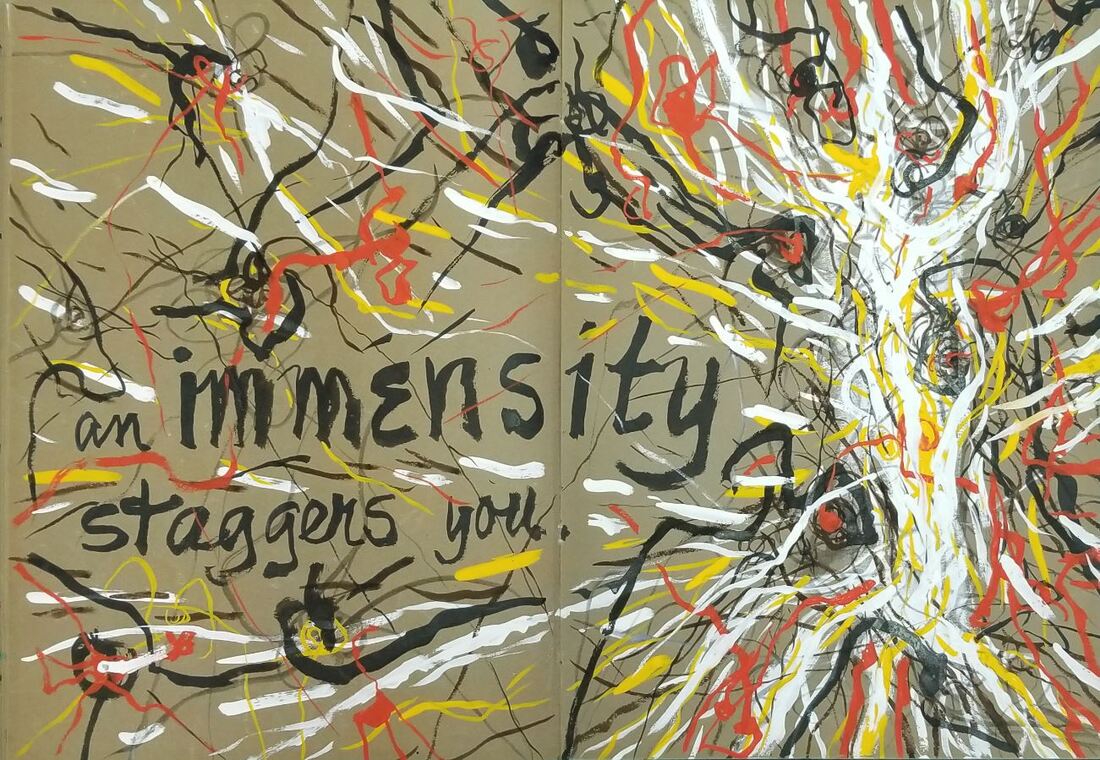

Paris Notebooks, 1963: Cave Drawings, mixed media on paper, 19 1/8 x 27 3/8 in. (open)

Verostko’s works in Paris included numerous notebooks that represent his interest at that time in automatic drawing, a technique used by some abstract expressionists in the 1950s and 1960s.

Verostko’s works in Paris included numerous notebooks that represent his interest at that time in automatic drawing, a technique used by some abstract expressionists in the 1950s and 1960s.

Elle Passe, 1965, pencil, crayon, gouache on paper, 22 x 30 in.

Artist Statement, Imaging the Unseen

Solo exhibition at Westlake Gallery, Minneapolis, 1972

Every human person bears within himself a jewel-like capacity—an imagination, a living spirit—that often lies dormant, unable to break through the busyness of everyday life. This human reality remains elusive because its peculiar mode of being transcends verbal and rational categories and we see its sparks come forth only occasionally.

These paintings and drawings emerge from interest in pictorial imagery that stimulates our awareness of and delight in the human imagination. The images contain no conscious symbolism. They are not charged with meanings. I have tried to achieve, in pictorial statement, the flow of “making up” an image and the delight of that human imagining that unfolds the image. In every instance, I seek to evolve an image that would be simultaneously unlike anything seen before, yet surprisingly believable in terms of its own reality. I believe that such imagery provides “experience clues” about the nature of realities that are outside the scope of rational consciousness.

Solo exhibition at Westlake Gallery, Minneapolis, 1972

Every human person bears within himself a jewel-like capacity—an imagination, a living spirit—that often lies dormant, unable to break through the busyness of everyday life. This human reality remains elusive because its peculiar mode of being transcends verbal and rational categories and we see its sparks come forth only occasionally.

These paintings and drawings emerge from interest in pictorial imagery that stimulates our awareness of and delight in the human imagination. The images contain no conscious symbolism. They are not charged with meanings. I have tried to achieve, in pictorial statement, the flow of “making up” an image and the delight of that human imagining that unfolds the image. In every instance, I seek to evolve an image that would be simultaneously unlike anything seen before, yet surprisingly believable in terms of its own reality. I believe that such imagery provides “experience clues” about the nature of realities that are outside the scope of rational consciousness.

Verostko

The Eikon Series

Left to Right: Eikon series (#111, #102, #110, #100, #106, #108), 1970s

acrylic with gesso base on wood

acrylic with gesso base on wood

The Greek word eikon (image) has been used traditionally to refer to the holy images associated with both ritual and private devotion in Eastern Christianity. These images were “sensible” forms through which the believer could be led to contemplate or participate in the sacred realities of his belief. The paintings in this show are titled Eikons not to suggest “holy” images, but rather that tradition of painting which strives to embody in some form of “sensible” image a reflection of realities that touch the human spirit but are outside our visible world.

In our complex twentieth-century life, the treasures of the spirit within us tend to be encumbered with objects, things, and everyday business. To enter one’s imagination, to play, to delight in the gift of the human spirit —these are “free” activities that break through that prison and nurture the human quality of life. Through these paintings and drawings, I have attempted to enter that imagining mode in the life of the spirit and to evoke some of its treasures.

In our complex twentieth-century life, the treasures of the spirit within us tend to be encumbered with objects, things, and everyday business. To enter one’s imagination, to play, to delight in the gift of the human spirit —these are “free” activities that break through that prison and nurture the human quality of life. Through these paintings and drawings, I have attempted to enter that imagining mode in the life of the spirit and to evoke some of its treasures.

Verostko

The Magic Hand of Chance

While the earliest electronic computers date from the 1940s, it was not until the Apple II in 1977 and the IBM 5150 in 1981 that mass-produced PCs became practical and affordable for individual users. With no software available for artists, Verostko set out to create an intelligent program capable of executing his own art-form ideas. The Magic Hand of Chance would be one of the first examples of generative art programmed with a PC. Its first public showing took place in a Minneapolis computer parts storefront window in 1983. It has been shown many times since, including Minneapolis College of Art and Design's 1986 Centennial Faculty Exhibition, the 2004 exhibition the Algorithmic Revolution at the Center for Art and Media Technology (ZKM) In Karlsruhe, Germany, and as a projection for the 2014 Northern Spark all- night arts festival held in the Twin Cities.

While the earliest electronic computers date from the 1940s, it was not until the Apple II in 1977 and the IBM 5150 in 1981 that mass-produced PCs became practical and affordable for individual users. With no software available for artists, Verostko set out to create an intelligent program capable of executing his own art-form ideas. The Magic Hand of Chance would be one of the first examples of generative art programmed with a PC. Its first public showing took place in a Minneapolis computer parts storefront window in 1983. It has been shown many times since, including Minneapolis College of Art and Design's 1986 Centennial Faculty Exhibition, the 2004 exhibition the Algorithmic Revolution at the Center for Art and Media Technology (ZKM) In Karlsruhe, Germany, and as a projection for the 2014 Northern Spark all- night arts festival held in the Twin Cities.

The Magic Hand of Chance, 1982 algorithmic routines written in BASIC with a first edition IBM PC for a CGA color monitor.

The Magic Hand of Chance was written in BASIC with a first-generation IBM PC. The master program occupies only 32kb of space, the size of a thumbnail digital photo. Limited to a 320-by-200 pixel screen and three colors per frame in its graphic mode, the Magic Hand generates surprisingly colorful bits of charm and humor with non-repeating visual improvisation and textual invention.

|

The Magic Hand of Chance, 1981–83, untitled dot matrix prints on bond paper, 11 x 8.5 in.

|

Between 1982 and 1986 Verostko became interested in “hard copy” or printed versions of his Magic Hand of Chance routines that mimed aspects of his own work as a painter. He made several prints from screen files and began to write software for building pictorial elements with lines and brush-strokes. The Magic Hand of Chance provided the kind of logic from which Verostko’s pen-plotted painting program would grow.

|

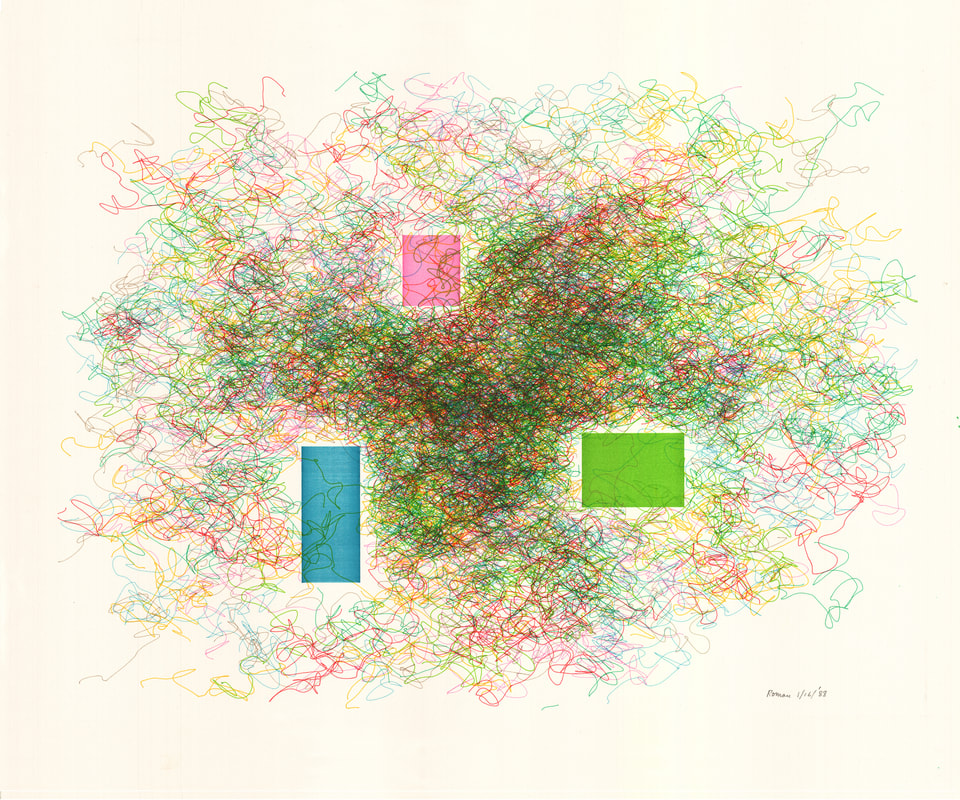

Untitled (AAG.D03), 1988, pen and ink plotter drawing, 24 x 22 1/34 in.

|

Sun Canticle, 1996, brush, pen, and ink plotter drawing with gold leaf, 13 x 19 in.

The central pen stroke was plotted with a fine brush and the gold leaf enhancement was applied by hand. The radiant algorithm for this drawing dates from 1986. |

Untitled, 1996, pen and ink plotter drawing, 13 x 19 in.

The coded parameters for this drawing were set by Verostko’s wife, Alice. |

WIM: The Upsidedown Mural

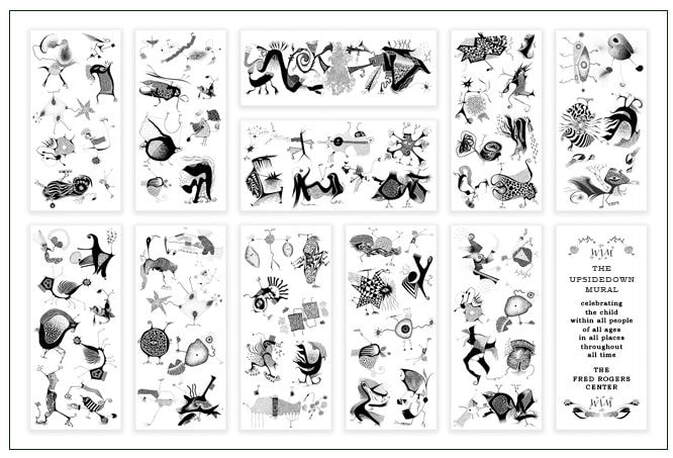

WIM: The Upsidedown Mural, 2008, digital print mounted on Sintra and Plexi, 12 panels, 96 x 48 inches each, Fred Rogers Center, Saint Vincent College, Latrobe, Pennsylvania

Inside the main entrance of the Fred Rogers Center at Saint Vincent College, the Upsidedown Mural rises two stories. This project, based on pen and ink drawings created by Verostko in the early 1970s, draws on the same core of whimsical drawings he presents in WIM: The Upsidedown Book (2008).

For the mural project, Verostko scanned his original drawings at a high resolution and then carefully retouched and scaled each image into working digital files. With these he composed fanciful groupings for eleven large panels scaled precisely for the wall.

Most of the originals were drawn with pen and ink in a 9-by-12 in. format on Strathmore Bristol 500. One of the large original drawings for the group was conceived as a mural for a school of music and now hangs in the executive offices of the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra. The pen and ink drawings belong to a transitional period in Verostko’s life following his withdrawal from monastic life and a move to Minneapolis. For him the 1970s were filled with experimentation and unfinished projects like this book with its suite of pen and ink drawings.

About the Fred Rogers Center

Established at Saint Vincent College in 2003, the Fred Rogers Center serves as a national and international resource for addressing emerging issues affecting children and families. Opened to the public in the fall of 2008, the building includes state of the art facilities for housing the complete archives of the late Fred Rogers, creator of the beloved television show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood (1968–2001). To learn more, visit fredrogerscenter.org.

For the mural project, Verostko scanned his original drawings at a high resolution and then carefully retouched and scaled each image into working digital files. With these he composed fanciful groupings for eleven large panels scaled precisely for the wall.

Most of the originals were drawn with pen and ink in a 9-by-12 in. format on Strathmore Bristol 500. One of the large original drawings for the group was conceived as a mural for a school of music and now hangs in the executive offices of the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra. The pen and ink drawings belong to a transitional period in Verostko’s life following his withdrawal from monastic life and a move to Minneapolis. For him the 1970s were filled with experimentation and unfinished projects like this book with its suite of pen and ink drawings.

About the Fred Rogers Center

Established at Saint Vincent College in 2003, the Fred Rogers Center serves as a national and international resource for addressing emerging issues affecting children and families. Opened to the public in the fall of 2008, the building includes state of the art facilities for housing the complete archives of the late Fred Rogers, creator of the beloved television show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood (1968–2001). To learn more, visit fredrogerscenter.org.

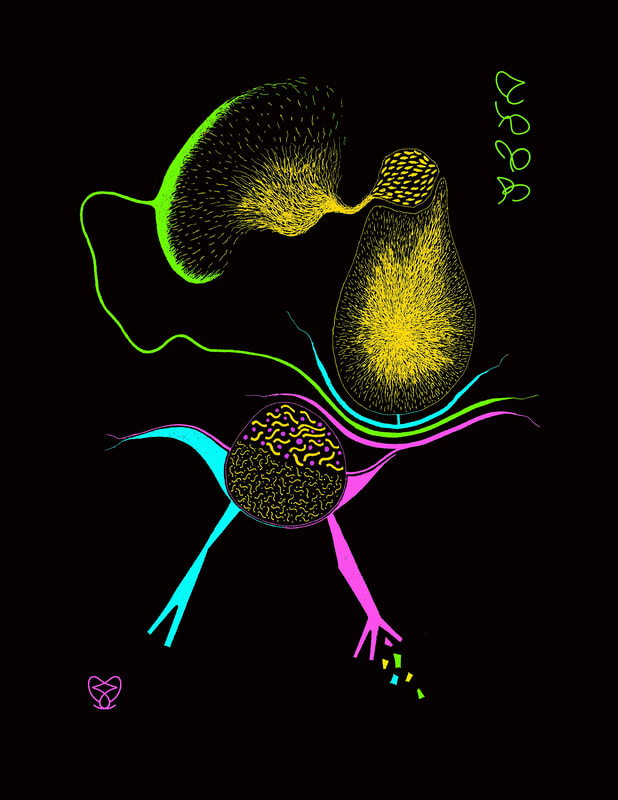

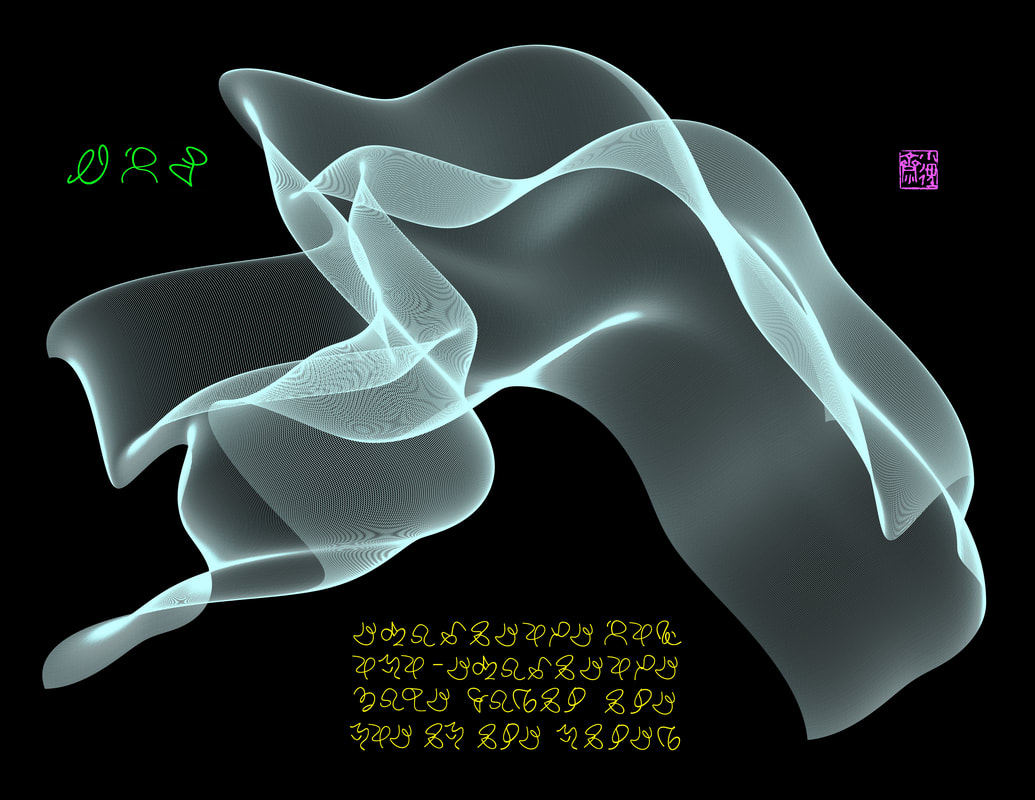

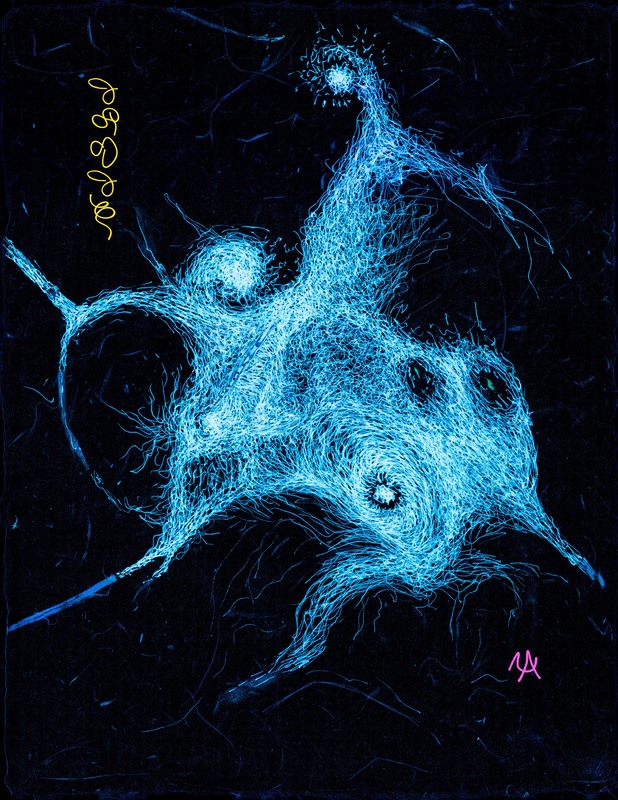

Digital Transformations

Left to right: Transformations: Celebrating Apollo 11, NASA series, 2016, archival pigmented print, 22 x 17 in., Transformations: Apocalypse of San Marco, 2016, archival pigmented print, 17 x 22 in., Transformations: The Cloud of Unknowing, 2018, archival pigmented print 17 x 22 in., Transformations: Wanderer, NASA series, 2016, 22 x 17 in.

These digital transformations draw on my work generated from all previous periods. Some employ scripting and drawing routines generated by my master software program, Hodos, and transformed into raster files for pigmented digital printing. The calligraphic scripts, drawn with the same coded procedures that generated the master forms, are presented as a form of “visual poetry.” In these examples the scripts speak “visually,” as it were, about “form qualities” that permeate the master form. These characters evolved, in part, from my experience teaching in China in the 1980s. Later I learned that Wang Dongling, who followed my twentieth -century Western art course in China, had undertaken to create works with the visual qualities of traditional calligraphy but they were not actually characters. Such work with “no-character” (feizi) have entered mainstream work by other Chinese contemporaries such as Gu Wen Da, who also followed my course in Hangzhou in 1985.

The Nasa series is created in memory of my brother Charles (1931–2017). His work with life support systems at NASA's Houston Space Center contributed to the success of the first flight to land on the moon in July 1969. The work Celebrating the Apollo 11 is a transformation of an early 1970s pen and ink drawing in my Imaging the Unseen series. Many of the drawings that appear in my Upsidedown Book and Upsidedown Mural were inspired by a growing interest, at that time, in what we might expect to encounter in outer space.

These transformations are original, limited edition, digital prints. They embody sixty-five years of my experience as an artist wrestling with visual form. As an artist, my work strives to achieve a form that invites us to savor a transcending moment in everyday, commonplace life.

The Nasa series is created in memory of my brother Charles (1931–2017). His work with life support systems at NASA's Houston Space Center contributed to the success of the first flight to land on the moon in July 1969. The work Celebrating the Apollo 11 is a transformation of an early 1970s pen and ink drawing in my Imaging the Unseen series. Many of the drawings that appear in my Upsidedown Book and Upsidedown Mural were inspired by a growing interest, at that time, in what we might expect to encounter in outer space.

These transformations are original, limited edition, digital prints. They embody sixty-five years of my experience as an artist wrestling with visual form. As an artist, my work strives to achieve a form that invites us to savor a transcending moment in everyday, commonplace life.

Verostko

Three Story Drawing Machine

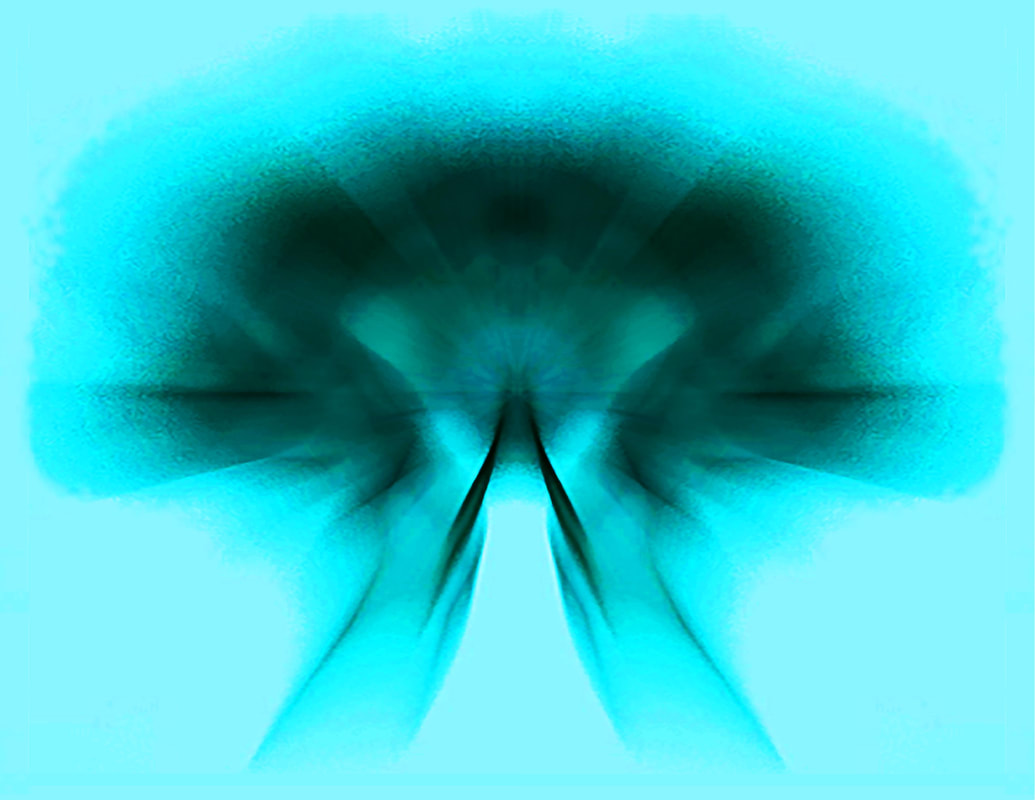

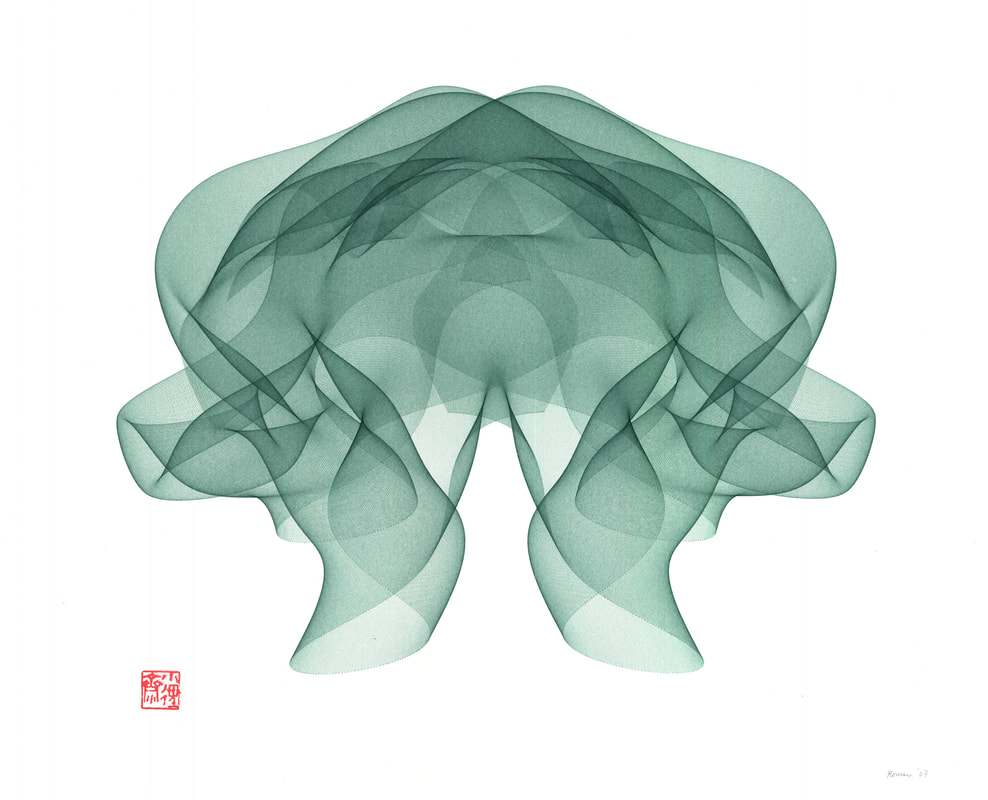

and Algorithmic Poetry, Green Cloud

and Algorithmic Poetry, Green Cloud

In 2011, Verostko was invited by Steve Dietz, founder and president of Northern Lights.mn, to participate in the first Northern Spark all-night art festival held in the Twin Cities. For this festival, which ran from sundown on June 4 to sunrise on June 5, they decided to project in real time an eight-hour drawing session onto the north side of the main building at MCAD. Viewers could watch the robotic arm of the pen plotter move across the paper and hear the sound of the machine as it worked tirelessly over the 705 minutes. As dawn approached, the routine ended, and the machine added twelve black calligraphic pen strokes. Finally, the artist impressed the finished piece with his Pathway Studio seal.

The final drawing, Algorithmic Poetry, Green Cloud, belongs to a series of visual poems that celebrate the ubiquitous information processing instructions that control most of today’s social systems, tools, and machines.

The final drawing, Algorithmic Poetry, Green Cloud, belongs to a series of visual poems that celebrate the ubiquitous information processing instructions that control most of today’s social systems, tools, and machines.

Three-Story Drawing Machine, 201, eight-hour video projection, presented by Northern Lights.mn as part of Northern Spark, Minneapolis College of Art and Design

Photo: Dusty Hoskovek, courtesy Northern Lights.mn

The Cloud of Unknowing, 2003, pen and ink plotter drawing, 29 x 23 in.

|

The exhibition continues:

|