Palimpsest Poetry |

|

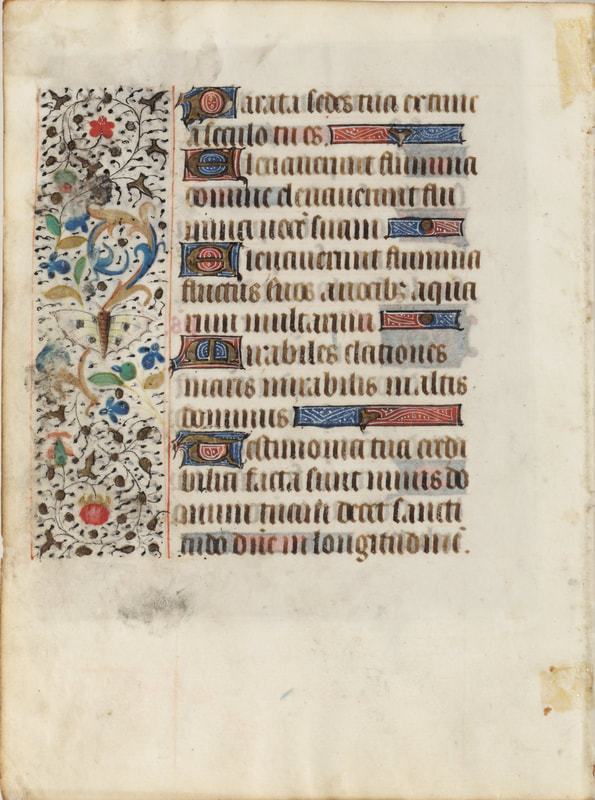

Book of Hours leaf

French, late 13th century Tempera, ink, and gold on parchment Latin Saint Vincent Special Collections |

Books – both printed and hand written – have long been recycled in service of the construction of newer volumes. Prior to mechanical printing, books were painstakingly copied by hand on a smooth surface made from calf, goat or sheep skin known as vellum. Those responsible for copying books inevitably made mistakes. Vellum allowed for unwanted text to be scraped off from the page with a knife enabling the scribe to write over the area. These eliminated sections of writing known as palimpsests can now be seen using ultraviolet light; frequently revealing a document’s layered history.

Because vellum was expensive and a highly durable material, medieval manuscripts were often cut up to serve as bindings for other books after the printing press revolutionized Europe in the mid-15th century. Fragmentology, or the study of how hand-written manuscripts volumes were often disassembled and at times recycled, enables researchers to learn how a specific manuscript was created, who may have owned it, and where it was written. This page from a medieval book of hours depicts a moth surrounded by filigree or the delicate, curvy line work resembling a stylized vine. These decorative embellishments are an example of marginalia – the outlying illumination, commentary, doodles or notations on the perimeter of a page intended to enhance the presenation or understanding of the text. The decorated initials in red, blue, and gold would have emphasized to its reader the importance and significance of these words. Learn more about traditional manuscript production and mechanical printing. |

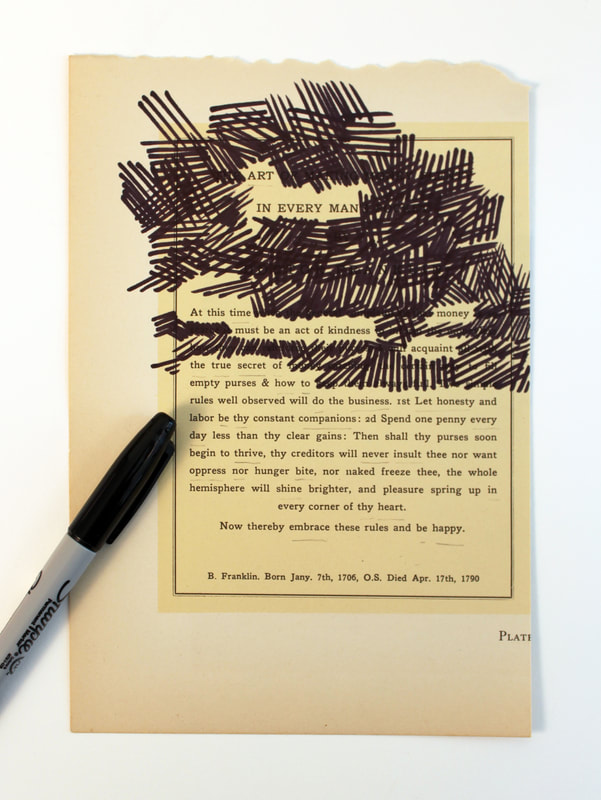

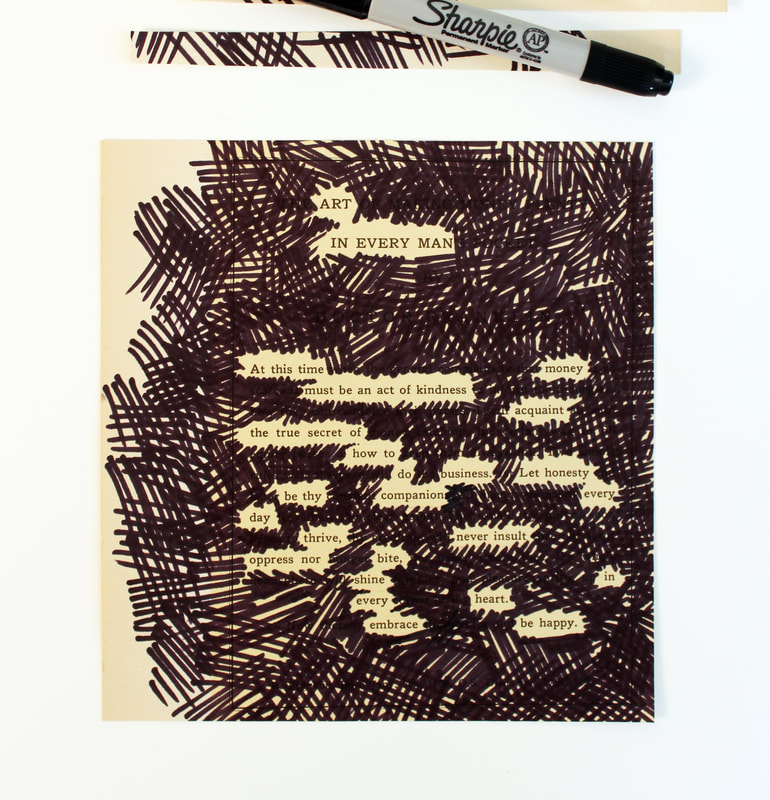

Blackout Poem / Using only the words on the page, recycle a piece of printed text by turning it into a work of art. Like a medieval palimpsest, your poem is created by layering new meanings on old materials.

Skim through the text and lightly underline the words or phrases that stood out to you with a pencil. It’s not necessary to read through the page for comprehension, rather read for words that are striking.

|

Ask yourself:

How might this text speak in a new way? What are the words saying to me? How can I sequence them in order to create a message? Using a pen, dark marker, white-out, or other media, eliminate the words that are not part of your poem. Be creative with the materials that you’re bringing into your project. Add layers of colored pencil, collage, crayon, string, glue/sand, paint, colored markers, etc. Embellish the area around your poem with marginalia – using designs, images, or symbols that further communicate the mood or ideas your poem evokes. |

|

Remember:

There’s no right or wrong way to create your poem. While you’re working with a structure, this project is not about the author’s intent. Therefore, it’s important to allow for your own thoughts, feelings, and ideas to emerge. Uncover unexpected meanings and make the text your own. Be patient with yourself throughout the process and don’t overthink your choices on the page. |

Studio Research / Using every page from W. H. Mallock's 1892 novel, A Human Document, artist Tom Phillips transformed a copy he found at a secondhand store into an entirely new work entitled, A Humement. Phillips' project redacts text and introduces new imagery to create a serendipitous vision that's part artists book, part collage, part painting, and part poetry. Find inspiration for your project by visiting the artist's website.